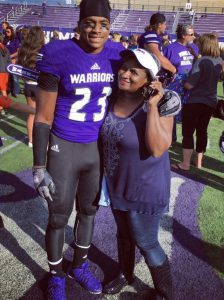

By Zach Bailey

Nervous energy fills my body as I wake up to the rustling of last minute packing. The worst thing that could happen is that we forget something.

My father, sister and I double- and triple-check everything, then climb in the truck and make our way out of Winona.

After an hour and a half (though it seems like an eternity), we reach the open field in Mazeppa, Minnesota, our destination. We are the first to arrive.

The time is 7:06 a.m. Mist falls upon the dew-filled grass as the sound of crickets fills the air on this early morning in May of 2009.

We unpack and change as more and more people begin to drive in to the lot. Two hours later the day begins.

My time is coming up, and I know what I must do.

I climb on the machine that will lead me to straddle the line between safety and danger, calm and fear, going through life and truly living life.

The 30-second board goes up, signaling the amount of time until the race starts as I bring life to the engine of my 65cc Kawasaki motorcycle.

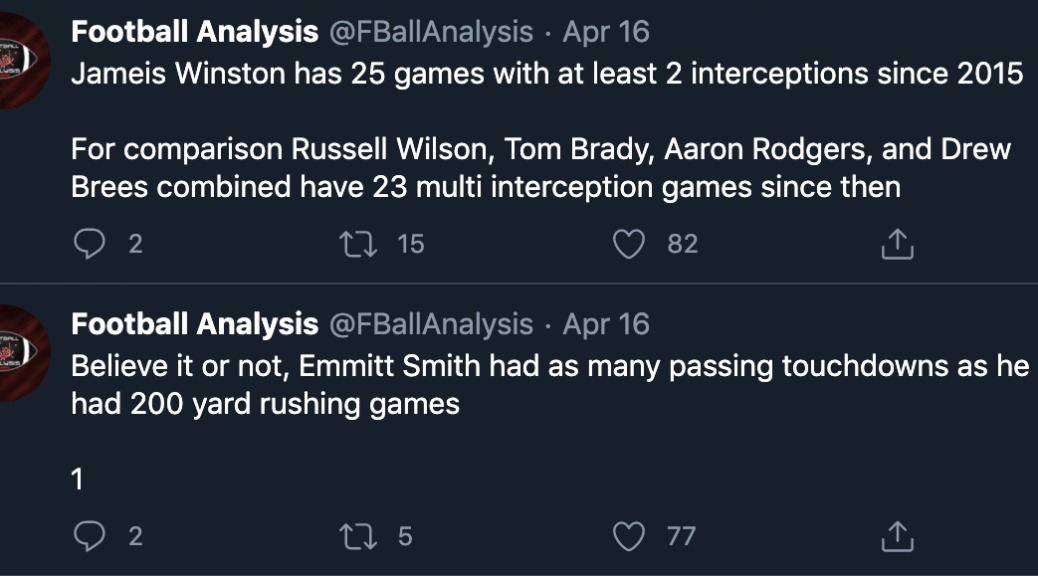

Every summer thousands of youth take part in different types of motorcycle races throughout the nation. These races include everything from motocross, which involves twists, turns and jumping over obstacles, to flat track, which involves sliding into corners at speeds of 40-120 mph.

Dan Bailey, my father and a lifelong motorsports enthusiast, is a personal supporter of youth in racing.

Bailey was first introduced to motorsports at a young age but was not initially on the motorcycle side of racing.

His father worked as a radio announcer in Dubuque, Iowa, and Madison, Wisconsin, where he began to cover events at the local county fairground dirt tracks. Through meeting people at the racetrack his father became friends with them and launched his career, which led to my father becoming involved in motorsports.

“When I was in second grade I saw a program on TV called ‘Wide World of Sports,’ where they covered a race from Millville, Minnesota, and it immediately made me think motorcycles were cool,” Bailey said. “Getting into stock car racing I became infatuated with motorsports, then in high school I saw a program on TNN called ‘Thursday Night Thunder,’ which was speedway motorcycle racing from Orange County Fairgrounds in Los Angeles. It was a cool combination of oval stock car track, but with motorcycles.”

From there, Bailey decided he one day wanted to make this a family affair.

“Then when we moved houses 13 years ago, I was looking for something we could do for fun together as a family, so I bought you the 70 [cc, child-sized motorcycle], Allie [my sister] the quad [four-wheeler], and me the 125 [cc, young adult-sized motorcycle] so we could do trail riding. Then we started getting involved in motocross racing and it exploded from there… Or, some would say, got out of control from there,” Bailey said with a laugh.

The gate drops on that cool, May morning, and I blast out of the gate.

My heart races as I follow one of my competitors down the start straight and into the first turn. All I can hear is the screaming of the small, 65cc cycles, and the continual pulsing in my eardrums caused by the mix of excitement and pure terror of what could happen.

I follow the other competitor through the twists and turns and the ups and downs of the first three laps, my eyes continually drawn to the bright orange of his rear fender. I follow close behind him at every straightaway and watch as he slowly pulls away through every turn.

A few turns before I reach the white flag (which signifies the last lap of the race), my rear tire slips out from under me. I feel myself begin to go over the handlebars, but I know that that will ruin my chances of finishing well during my first real race. With all my might I hold on and save myself from what could have been.

I regain control and race to the white flag.

One. More. Lap.

“Overall, I believe [youth in racing] is a positive thing,” Bailey said. “It broadens horizons and gives kids the chance to explore something new that is not common or typical. It’s a sport that is a little different and out on the fringe. There aren’t as many families in motorsports as in baseball or football.”

Bailey continued by saying that, along with being a different type of sport to be involved in, there were multiple other reasons as to why he brought his family into the world of motorcycle racing.

“One is it’s just fun. Second, I think it can be a true teacher for the realities of life. If you want to succeed you have to work hard at it. Just because you do it doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be good or win,” Bailey said. “You have to learn about what you’re doing, learn about the motorcycle, the rules, and the concept of competition. Also, at a young age, it teaches kids good mind, hand and eye coordination. It’s kind of like playing an instrument. You have to do all these different things at the same time to successfully ride a motorcycle, and then push it to its limits.”

According to Philip Rispoli, founder of Coolskunk, which is a sports promotion organization and racing team, motorcycle racing is not a sport that kids should be thrown into nonchalantly.

“They need the right combination of parental support and the right rider attitude,” Rispoli stated in an interview with the American Motorcycle Association (AMA). “The parents must be committed to supporting the rider, and the rider needs that twinkle in the eye.”

Rispoli continued by stating that attitude is a key attribute to having a child enter the world of racing.

“If you end up with a world champion, great, but that’s not what this is about,” Rispoli stated. “We want to build a winner both on and off the track.”

I race past the white flag and grab a handful of throttle to clear one of the smaller jumps on the track, one of the few I’m not scared to do so.

Beneath me, out of the corner of my eye, I see a flash of orange off to the side of the track. By the time my tires hit the ground, the flash is already out of my memory. A passing thought which may as well stay forgotten.

Gaining more confidence with each turn, I slowly begin to race faster and jump farther. Finally, what seems like a lifetime from when the gate first dropped (even though it has been 10 minutes at most), I round the final corner and race through the checkered flag, not letting off the gas until I’m sure I’ve passed the finish line.

I ride back to the truck, climb off my metal steed, and begin to take off the seemingly hundreds of pounds of protective gear that I wear during each race.

Out of the corner of my eye I see my dad running up to me, thumbs raised and a huge grin across his face.

We high-five, hug and talk about how everything went and what I can improve for next time.

A motorcycle rides by in the background.

A flash of orange.

Memories flood back to me as I look over at my dad.

“Hey dad,” I say, simultaneously nervous and confused. “I think I passed the leader on the last lap.”

Though Bailey is a supporter of introducing people to motorcycles at a young age, he does understand that it has both its pros and cons.

“[Motorcycle racing] has similar pros to any other sport or community involvement. It encourages interaction with peers, helps people to socialize and interact with new people, as well as understand they can still be friends with people even though they might lose to them. Also, if someone becomes good at any sport, it teaches them to be gracious winners, not egotistical.” Bailey said. “On the other side, it can potentially be dangerous and it’s pretty expensive, there’s no denying that.”

As Bailey said, the one factor to keep in mind is the potential risk of having a child associated with motorcycle racing.

According to a study by the American Academy of Pediatrics titled, “Youth motocross racing injuries severe despite required safety gear,” 85.7 percent of patients in a 2016 study were found to have been injured during a motocross competition. The patients, averaging 14 years in age, were all wearing the required safety equipment. Of those injured, just under three-quarters had received bone fractures or dislocations, and just under one-half were given concussions.

Even with the facts, however, Bailey plans on continuing racing as long as he and his family are healthy, able and having fun.

My dad smiles and pats me on the shoulder.

“You did well during that race,” he says, a bit of sadness creeping into his eyes. “But I’m sorry, Zach-Attack, I don’t think you won that race. Don’t worry, though, winning isn’t everything. All that matters is that you had a good time.”

I shrug it off, saying that he’s probably right. It does not matter, though; it was my first race and I had a good time, so I can successfully mark this off as a good day.

We go about the rest of our day at the track, I finish off the rest of my races, then as the sun slowly begins its falling action, marking the day as early afternoon, we begin to pack up and head to the main shed for trophies.

I walk up to the lady at the window, tell her my name and what classes I raced and wait in anticipation. She tells me it will just be a minute, so I take in the scene.

Off to my right, a father yells at one of the counter workers, wondering why his son does not receive a ribbon for participating. The kid elbows his dad, trying to say that it’s fine, he does not even want one, but the father pays no attention to him.

A tap on the shoulder startles me as I’m knocked out of my daze.

The lady at the window places a large, gold trophy in front of me. Scrolled on the front, “First Place.” I look at her, then my dad in confusion.

“You passed the leader on the last lap of this race,” the lady says, looking down at the scorer’s sheet. “This means you won.”

Zach Bailey is a senior marketing and mass communication-journalism major from Winona, Minnesota. He is currently the editor-in-chief of the Winonan, the Winona State student newspaper, as well as a member of Sigma Tau Gamma fraternity. In his free time, he enjoys racing motorcycles, playing guitar, reading and watching movies. He hopes to one day work for the New York Times and become a published author.