by Samantha Stetzer

Jenna McMillan believes her life would have been different if someone would have just talked to her.

McMillan grew up in Winona, Minnesota, with what she called “a good family.” Her mother was a nurse, her father was involved in real estate and she had a stepfather who was an attorney.

She graduated from high school and eventually attended Winona State University where she made the dean’s list and graduated with a degree in marketing, playing to her business strengths.

When McMillan was 14 years old, she started drinking and doing drugs. When she was 15, she ran away and was arrested. She was sent to a halfway house where she spent the summer between junior high and high school.

The next year she said she found some better friends in school, but continued to abuse substances. When she graduated high school, she was introduced to methamphetamine, and throughout college became a casual dealer—an unfortunate use for that business-oriented mind, McMillan said.

Soon, she was more than a casual dealer. She became addicted to the lifestyle that fueled her drug addiction until her home was raided and she was arrested at 28 years old for selling meth.

If convicted, McMillan could have faced up to seven years in prison.

Instead, she was given the opportunity to face her addiction, work in the community and only had to go to jail for a year. She has been sober now for seven years and works with chemical dependency in the Minnesota Teen and Adult Challenge program, engaging with teens about substance abuse and the issues it can cause.

McMillan said if people had talked to her about drug use before she started becoming a heavy user or even took her first sip of alcohol, most of her life would be different. Discussing addiction when she was growing up was a hush-hush topic.

Now 42 years old, McMillan said she has seen the positives of initiatives that promote prevention in Winona County. Even though she said she would like to see more prevention efforts, she believes those standing up against addiction have been fighting for a worthwhile cause.

Responding to the need together

Winona County Attorney Karin Sonneman said she does not believe in reinventing the wheel. She believes in using the whole wheel.

Since being elected as the county’s first female county attorney, Sonneman has made it a mission to implement what she calls “smart justice.”

“I’m not a lock-em-up kind of prosecutor,” Sonneman said. “There’s no reason to lock somebody up that has a mental illness or who has a drug problem that is not committing crimes of such a serious nature that they can’t be helped.”

According to Sonneman, a big part of prevention is targeting children in the area who are the most susceptible to mental health and substance abuse based on the adverse childhood experiences (ACE), such as a parent using drugs or a history of abuse in their home. According to Sonneman, the more ACEs a child has, the more likely they are to use drugs and alcohol.

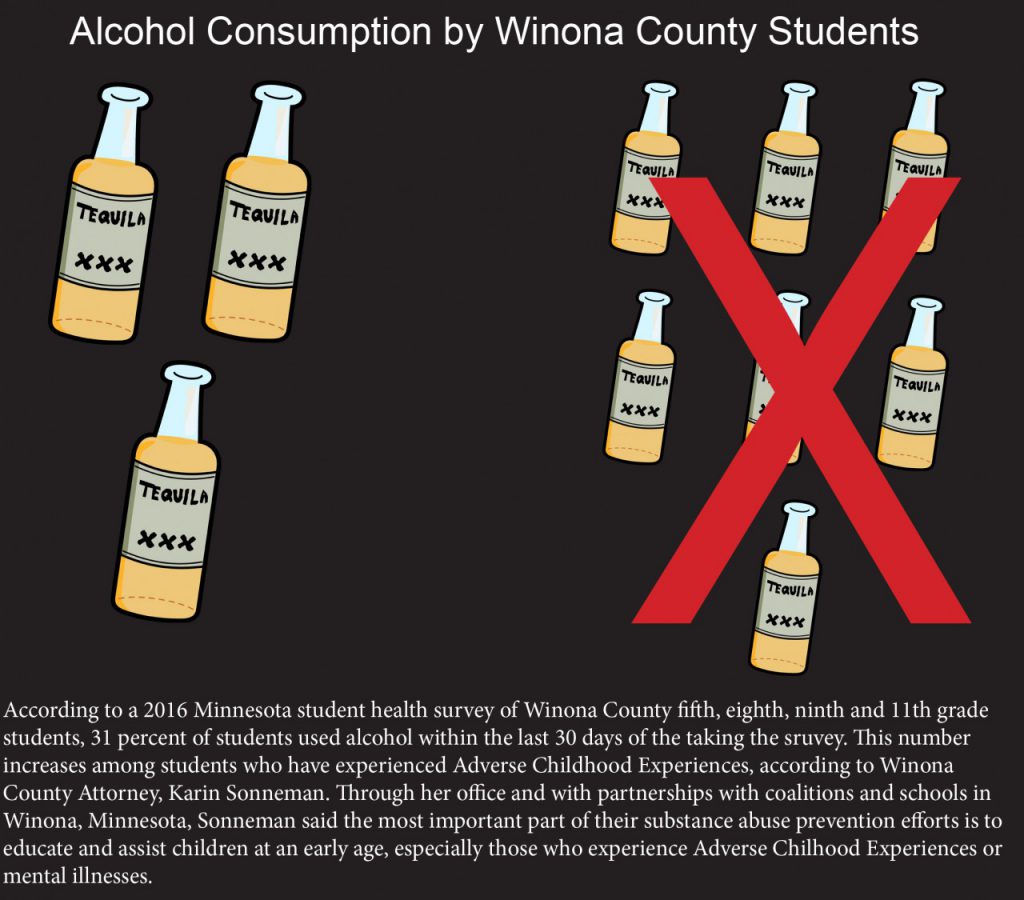

A 2016 Minnesota Student Health Survey of a fifth, eighth, ninth and 11th grade students in Winona County, found that as the number of ACEs a child experiences grows, so does their likelihood to use substances, with a slight dip between one ACE and two ACEs before continuing to rise again.

According to the survey, in Winona County 36 percent of children have experienced at least one ACE in their lifetime.

Furthermore, the study found alcohol was the drug of choice for approximately three out of 10 Winona County students within the 30 days before the survey. The average of alcohol use in Winona County was reported to be almost six percent higher than the state average. Usage numbers for tobacco and marijuana were both one to two percent higher in Winona than the state average.

Through the Winona County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, a group of justice experts in the Winona area who review and advocate for justice reform and policy, and her office, Sonneman said she tries to partner with area coalitions and organizations to provide what she views as fair justice for both sides of the legal system. By working together, she said she believes a wider net of prevention and justice reform can be cast in Winona County.

“Because we can do it on a collaborative basis, why reinvent the wheel? Or duplicate efforts,” Sonneman said. “So we’re planting seeds with the prevention early on.”

For Sonneman, the work begins at the local schools.

Sonneman said her office and the county court system host Law Day for local sixth grade students in Winona County, making them active participants as judge, jury, attorney and prosecutor for a pretend case involving a certain theme, such as theft or prescription drug use. The students follow the criminal justice system from beginning to end, in what Sonneman called a “scared straight but better” system.

The County Attorney’s Office also works with Winona State University for its partners in prevention program, which aims to educate college students about substance abuse on college campuses, according to Sonneman.

A large part of prevention, Sonneman said, is working to help treat mental illness and to prevent or help those who might self-medicate with drugs and alcohol.

The county was recently awarded a grant to help treat mental illness at the jails more efficiently, which can significantly help halt the “rotating door” of previously convicted criminals in the justice system, Sonneman said.

When an addict is receiving the help they need for their co-occuring addiction and mental illness, Sonneman said the county could prevent future issues and crimes from happening.

The idea has caught on at the local schools, according Mark Anderson, principal at Winona Senior High School. Sonneman and Anderson are both board members at Winona County Alliance for Substance Abuse Prevention, a drug and alcohol prevention and treatment coalition under the Winona County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council.

According to Anderson, at the high school level, most of the prevention against drugs and alcohol is not an outright campaign against abusing the substances. Instead, it is done through screening for mental health issues.

Through the screenings, Anderson said school professionals can determine which students need help and how parents and those students can seek resources to help the student find constructive ways of monitoring and managing their mental illness for academic and personal success.

From Anderson’s perspective, he said he believes the school should help a student with their mental health diagnosis and proactive ways to manage it in order to help the student engage more in their educate and creating a more productive life for themselves.

Anderson said the school district requires students to take health classes in seventh, eighth and 11th grades that cover topics like alcohol and drug abuse, but mental health is discussed starting as early as fifth grade.

Grade school students in the district used to participate in Drug Abuse Resistance Education, hosted by the Winona County Sheriff’s Department, according to Winona County ASAP Program Coordinator Phillip Huerta. Since the program has proven to be less effective than hoped, most school districts in the area have dropped the program. Lewiston-Altura Public School District is the only district in Winona County to still host the program.

While the focus of prevention at the high school level in Winona lately has been on mental health and what Sonneman and Anderson agree can be the root of addiction, students are also exposed to the consequences of substance abuse through programs like a mock crash.

Partnering with Winona County ASAP, the mock crash uses student actors to play the part of you people who drink and drive and eventually kill a friend due to substance abuse.

Both Winona County ASAP and the high school are working to bring the programming back to the high school this spring, in time for prom, according to Anderson. They hope they can add a personal story of loss to the crash program to really impact students.

Forced to be an advocate

For the city of Lewiston, Minnesota, it took a young man to lose his life for prevention to become an important focus for its residents, according to Winona County ASAP Program Coordinator Phillip Huerta.

Jonathan Mraz was a high school student in Lewiston who had hopes of someday becoming a teacher or a nurse, according to his mom, Dede Mraz. He was friends with most people, realizing when his classmates needed a friend.

His life was cut short by a train when he was stumbling home drunk and high after a night of uncharacteristic partying, his mother said—a party where another parent encouraged and supplied the alcohol for the students.

The community of Lewiston rallied around the Mraz family and Jonathan’s story,

Huerta said. For three to five years after his death, Jonathan was a reminder of the problems that can stem from using drugs or alcohol, and his mother still makes sure people do not forget it by speaking about her experience, Huerta said.

Huerta and Anderson both said they hope Dede Mraz will help the coalition with their mock crash this spring, to help bring a face to the tragedy of teen drinking.

“They’ll see tears. They’ll see the pain that the mother still carries to this day about it,” Anderson said. “And they’ll hear how emotional it is and how devastating it is for somebody to lose somebody because of something like that.”

The Lewiston community felt satisified with their efforts, Huerta said, since there were no tragedies due to substance abuse happening since Jonathan’s death. According to Huerta, the community’s prevention efforts tapered off after a couple years following Jonathan’s death, but Dede Mraz is still active in reminding students and their families to not support drinking and the use of drugs through the “Parents who Host, Lose the Most” campaign.

According to Huerta, students helped the coalition with this campaign by bombarding liquor stores and their bottles with stickers for the parents who host campaign, in what Huerta calls “sticker shock.” The students “shocked” the community with about 1,400 stickers, Huerta said.

It was a small gesture, Huerta said, but it was one he said that could change minds and impact the community through support.

“There are so many good ideas that are brought to the table, but our teams right now, even with a handful to a dozen people, it’s hard to do so much,” Huerta said.

Fighting with little funding

Huerta has seen a little money go a long way.

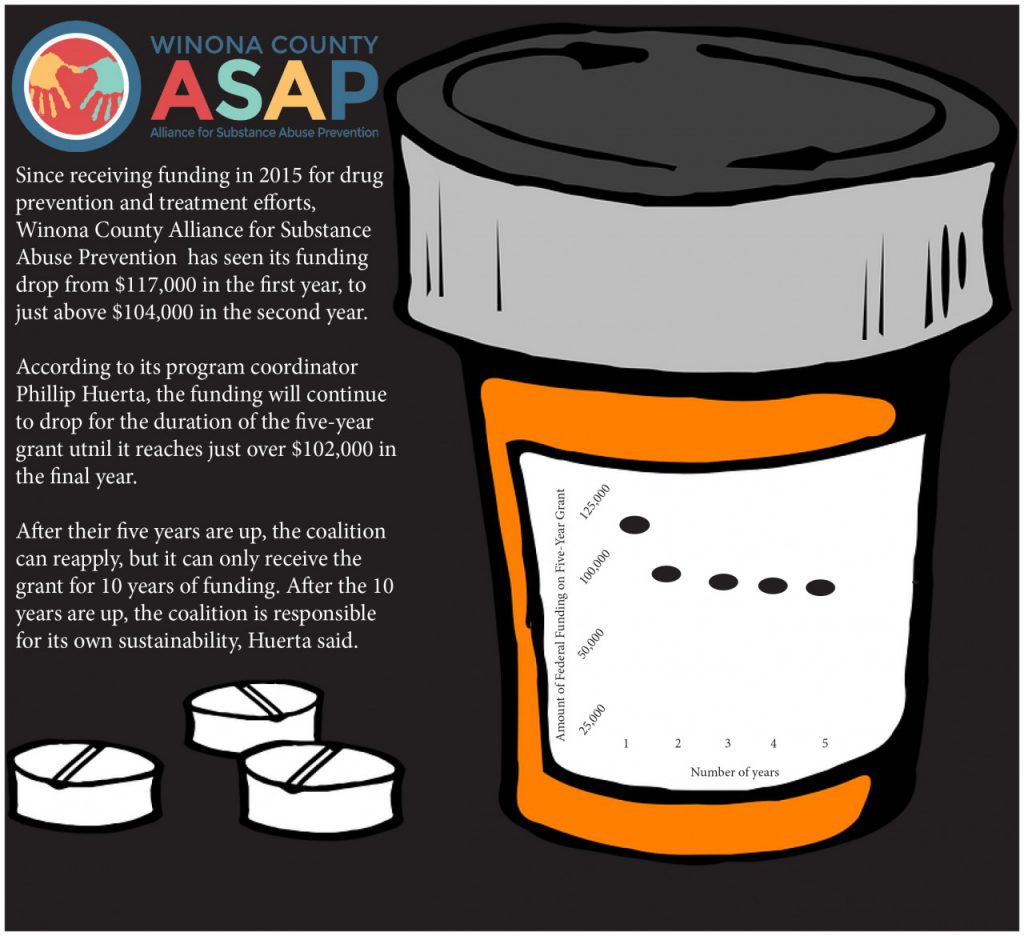

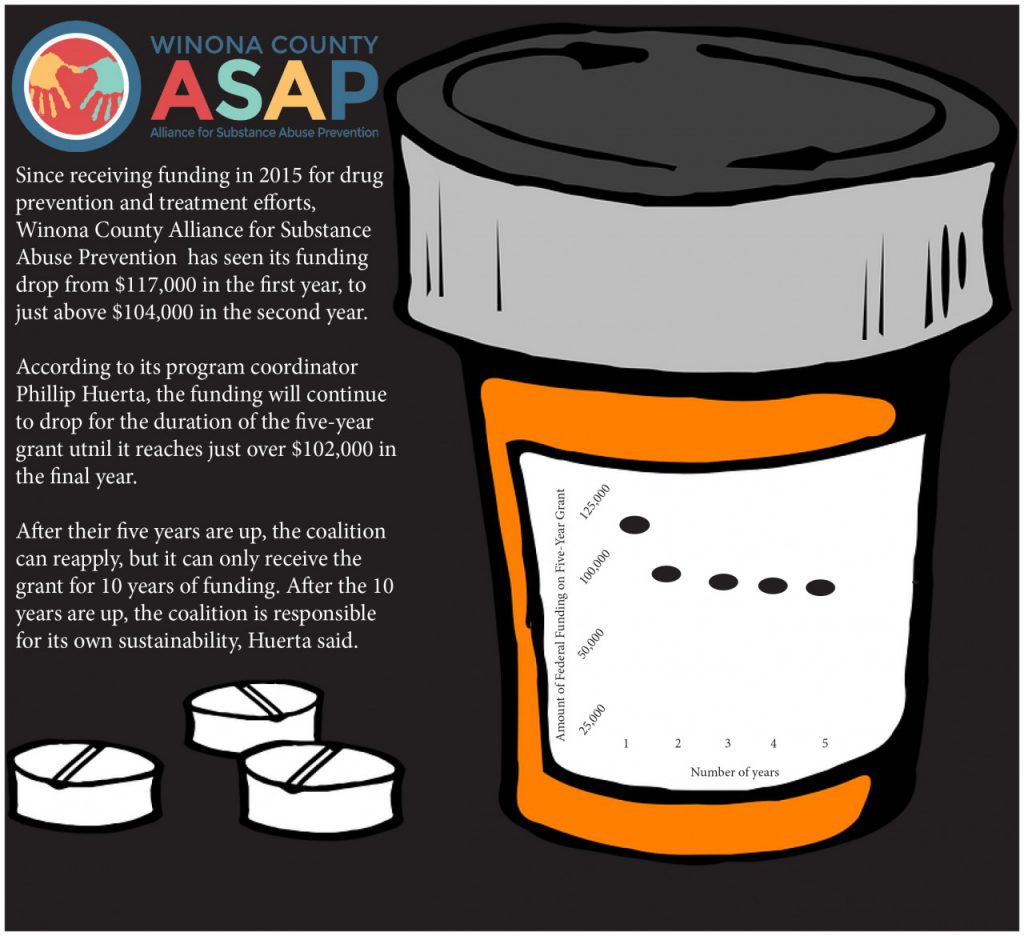

As program coordinator of Winona County ASAP, Huerta said even with only roughly $100,000 for all the prevention efforts the coalition is hoping to fund, it cannot provide all the programs the coalition would hope to bring to the community.

Huerta said he has believed in the strength of the people in the community to get the job done since the coalition became the forefront of drug prevention efforts in Winona County.

For the last two years, the coalition has been funded by a federal grant. The first year the coalition was awarded $117,000, but as the years on their five-year grant pass, the money they receive every year decreases. The last year of funding will be just over $102,000.

In 2016, the coalition was given just over $104,000 for their prevention efforts. According to civic and volunteer chair on the Winona County ASAP board of directors Beth Moe, the coalition cannot spend that money on providing the programming, but rather it has to be used to pull everything together, such as fliers or food for the event.

“The things we do don’t cost a lot, but they do cost something,” Moe said.

Moe said she fears what will happen to their funding now that a new presidential administration has taken over at the federal level.

With the funding they have now, Huerta said prevention can still reach a high number of students to be beneficial.

“Something that I want to remember throughout this whole process is that we did a lot with little money before,” Huerta said. “It’s doesn’t take a lot to do a lot, especially when you have people in the community that really care and want to send a good positive message.”

The main focus for that positive message within the coalition was initially on targeting alcohol and prescription pill usage by students in middle and high school.

Since alcohol has been heavily studied, Huerta said, prevention efforts against its use are the most accessible and effective.

The coalition is now shifting its focus to marijuana, specifically focusing on the Garvin Heights location, which has been identified by students as a hotspot for the drug, Huerta said.

“For marijuana, we need to understand it a little better in Winona because it’s a new topic for a lot of communities,” Hureta said. “We need to learn what does marijuana look like more specifically in our area and how can we address it, because, again, there’s also not a lot of evidence-based strategies out there.”

The coalition also had support from local and county governments in terms of creating policies to keep synthetic drugs like “turbo” off the streets in a more effective manor, Huerta said, part of the work Sonneman did after being first elected.

Better, but still a ways to go

For addicts like McMillan and Max Ruff, sharing their story is part of giving back to the community they were arrested for taking so much from, according to Ruff.

For Ruff, his addiction story begins at 12 years old when he first began taking Adderall and drinking alcohol. It ended on Sept. 27, 2014, when he was found passed out in a puddle of water in the woods near Kellogg, Minnesota, borderline hypothermia setting in and some meth in his cheek after a high speed chase that began in Winona.

Through the Winona County Drug Court, a program that uses intensive methods of treatment for addicts to help them obtain educational and workforce goals, and Narcotics Anonymous, Ruff is now 29 months sober and shares his story whenever he can.

Ruff talks to the community through meetings, forums and at appearances at local schools, using a lesson he has learned while in Narcotics Anonymous.

“You can only keep what you have by giving it away,” Ruff said.

While at a recent speaking event at the Winona Area Learning Center, Ruff said he had a student in tears while they were discussing the impacts of racism on this student. Ruff said he reminded the student to not give the racism power, because when he gave power to his addiction, he lost.

McMillan said she opens up a dialogue with local teenagers she sees at the Minnesota Adult and Teen Challenge and said she volunteers for Winona County ASAP’s board of directors.

McMillan said she would like to see more happen involving recovering addicts and connecting them to students who are on the boarder of isolation and substance abuse. She said she believes if someone had taken the time to talk about it with her, she might not have experienced what she did.

Both recovering addicts said they believe conversations about substance abuse should never stop, no matter what kinds of prevention efforts are used. With the stigma surrounding abuse starting to fade, McMillan said she believes more people feel comfortable opening up for help before large issues occur.

As long as prevention staves off the raid of a 28-year-old meth dealer’s house or prevents hypothermia for a 116-pound man over some meth in his cheek, both recovering addicts agree the solution is beneficial.